Projects

Evolution of synchronous and asynchronous flight

Some orders of insects have evolved specialized flight muscle that allows them to flap their wings at hundreds of times per second, exceeding conventional neuromuscular speed limits. This muscle is called ‘asynchronous’, since it contracts multiple times for every one neural signal. In contrast, most slow-flapping insects are ‘synchronous’, and receive a single neural control signal per wingbeat. We reconstructed the ancestral state and evolution of flight muscle types across a recent insect-wide phylogeny and found that asynchronous muscle likely evolved once originally, and there have been many subsequent reversions to synchrony. We then looked at a ‘secondarily synchronous’ order - Lepidoptera - to see if we could find evidence of latent asynchronous behavior in their flight muscle. We did, and we used this discovery to develop a biophysical model of how transitions between synchrony and asynchrony could have occurred in flight muscle. Finally, we applied this model to demonstrate transitions in robotic flapping wings.

Some orders of insects have evolved specialized flight muscle that allows them to flap their wings at hundreds of times per second, exceeding conventional neuromuscular speed limits. This muscle is called ‘asynchronous’, since it contracts multiple times for every one neural signal. In contrast, most slow-flapping insects are ‘synchronous’, and receive a single neural control signal per wingbeat. We reconstructed the ancestral state and evolution of flight muscle types across a recent insect-wide phylogeny and found that asynchronous muscle likely evolved once originally, and there have been many subsequent reversions to synchrony. We then looked at a ‘secondarily synchronous’ order - Lepidoptera - to see if we could find evidence of latent asynchronous behavior in their flight muscle. We did, and we used this discovery to develop a biophysical model of how transitions between synchrony and asynchrony could have occurred in flight muscle. Finally, we applied this model to demonstrate transitions in robotic flapping wings.

Structural damping in insect exoskeleton

Insects like moths deform an elastic exoskeleton with their flight muscles to move their wings efficiently. But, deforming any real material results in energetic losses to internal damping, and phase lags between force input and movement output. In this project, we characterized damping in hawkmoth exoskeleton under unsteady conditions, to understand how moths control behavior in situations where they must modulate their wingbeat frequency (takeoff, landing, in response to a gust of air, etc). We found that the exoskeleton exhibits frequency-independent structural damping in both steady and unsteady regimes, potentially simplifying motor control for moths performing frequency modulation behaviors.

Insects like moths deform an elastic exoskeleton with their flight muscles to move their wings efficiently. But, deforming any real material results in energetic losses to internal damping, and phase lags between force input and movement output. In this project, we characterized damping in hawkmoth exoskeleton under unsteady conditions, to understand how moths control behavior in situations where they must modulate their wingbeat frequency (takeoff, landing, in response to a gust of air, etc). We found that the exoskeleton exhibits frequency-independent structural damping in both steady and unsteady regimes, potentially simplifying motor control for moths performing frequency modulation behaviors.

Resonant mechanics of moths

Insects have long been thought to flap at their resonant frequency. In theory, flapping at this frequency allows them to fly efficiently, at the expense of the ability to modulate the frequency of their wingbeats. A helpful analogy is how you don’t have much control over the frequency you swing at on a swing set, and its very hard to change the frequency at which you swing. This is in part because of resonance. In insects, few attempts have been made to experimentally validate whether resonant wingbeats are actually the norm. We found that hover-feeding hawkmoths are likely flapping significantly above their resonant peak. This enables sustainable flight while maintaining the ability to modulate frequency, which may be important for species that must track moving flowers in the wind.

Insects have long been thought to flap at their resonant frequency. In theory, flapping at this frequency allows them to fly efficiently, at the expense of the ability to modulate the frequency of their wingbeats. A helpful analogy is how you don’t have much control over the frequency you swing at on a swing set, and its very hard to change the frequency at which you swing. This is in part because of resonance. In insects, few attempts have been made to experimentally validate whether resonant wingbeats are actually the norm. We found that hover-feeding hawkmoths are likely flapping significantly above their resonant peak. This enables sustainable flight while maintaining the ability to modulate frequency, which may be important for species that must track moving flowers in the wind.

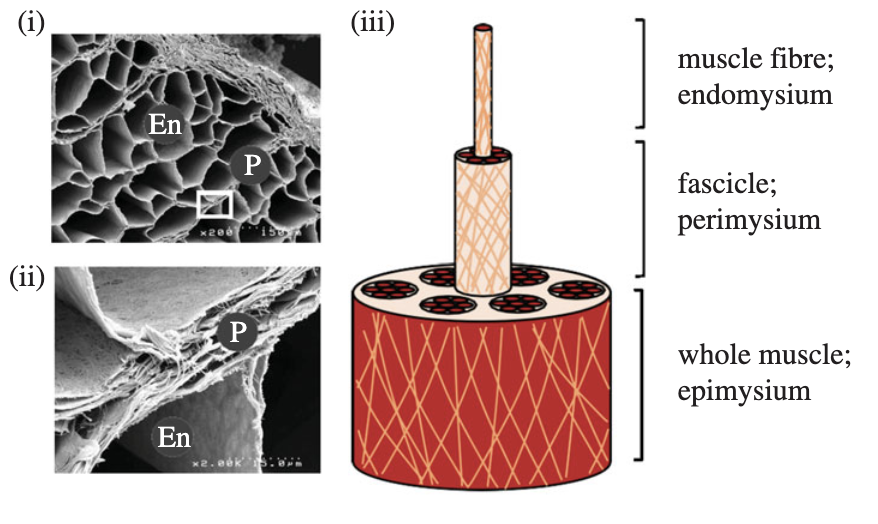

Fluid-ECM interactions in skeletal muscle

Muscles, like many biological tissues, are bags full of water. When a muscle contracts, it displaces this water, casuing pressure increases and affecting the development of force. We asked whether the reverse is also true: do muscles change their length when they are artificially pressurized? We increased muscle fluid volume by placing frog muscles in hypotonic solutions so they swelled due to osmosis. We found that these muscles produced increasing force at constant length and shortened under constant force as they took in water.

Muscles, like many biological tissues, are bags full of water. When a muscle contracts, it displaces this water, casuing pressure increases and affecting the development of force. We asked whether the reverse is also true: do muscles change their length when they are artificially pressurized? We increased muscle fluid volume by placing frog muscles in hypotonic solutions so they swelled due to osmosis. We found that these muscles produced increasing force at constant length and shortened under constant force as they took in water.